Abstract

Introduction

We discuss a case of a young male with juvenile SLE who presented with acute changes in mental state and was diagnosed with MAS/Secondary HLH and aHUS, a rare occurrence. This is the first instance of a case report in this presentation that we are aware of.

Case presentation A 28-year-old with history of pericardial effusion of unclear etiology presented with acute encephalopathy. He lost 50lbs in 7 months. He denied any visual changes, chest pain, shortness of breath, fevers, night sweats, chills, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain or numbness.

Admission vitals were 98.2 degrees fahrenheit, blood pressure 75/39, pulse 91, respiratory rate 24 with 100% oxygen saturation on room air, and body mass index 21.63 kg/m2. During the physical evaluation, he was awake, attentive, and oriented. He looked older, untidy, and cachectic. His eyes were pale and anicteric. Unremarkable physical exam.

Blood smear, bone marrow biopsy, HIV, and other viral panels were requested. Fluids, pressors, and antibiotics were given for septic shock. His hemoglobin decreased to 6.5 without a documented hemorrhage.

High dose steroids and eculizumab (with meningococcal vaccination) were given. Weaned off pressors, renal function improved, downgraded to floors.

ICU was recalled for seizure-like activity. We considered SLE cerebritis, steroid side-effect, PRES and ischemic event.

Mental condition deteriorated, requiring intubation, central line replacement, plasmapheresis, and fluids.

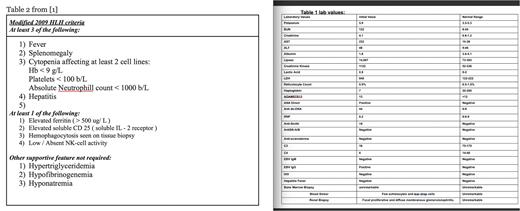

The patient's clinical picture is consistent with macrophage activation syndrome (MAS)/secondary Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) related to Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE).

Discussion HLH includes familial and secondary HLH, which includes MAS. MAS refers to autoimmune/autoinflammatory HLH1. MAS is only caused by acquired factors, while HLH is caused by inherited and acquired factors.

HLH can be inherited or acquired (secondary). Secondary HLH is caused by infections, cancers, and autoimmune disorders1. MAS is SHLH. Similar clinical features make diagnosing MAS-associated and active SLE difficult2.

According to the PRISMA flow chart3, only 28 reports have linked MAS to SLE. We found no literature on SLE-related MAS and presented atypical HUS.

MAS has been linked to sJIA, Kawasaki illness, adult-onset Still's disease, Sjögren's syndrome, dermatomyositis, mixed connective tissue disease, and systemic sclerosis. SLE causes 0.9%-4.6% of MAS cases. Once per million people per year4.

Difficult diagnoses can lead to delayed or inadequate care. Clinically, MAS and SLE are similar. Hyperferritinemia provides 100% sensitivity and specificity for detecting MAS-associated SLE5.

SHLH lacks treatment guidelines. MAS in SLE patients is similar. In severe or refractory cases, high-dose glucocorticoids are followed by cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, anakinra, etoposide, and IVIG. In severe cases, MAS patients use plasma exchange6.

TMA is an SLE/APS complication. TMA causes capillary and arteriolar thrombosis from endothelial injury. Hemolysis, thrombocytopenia, kidney damage, and other end-organ dysfunction result from diffuse thrombosis7. TMA includes TTP, HUS, and complement-mediated TMA. This group includes atypical HUS (aHUS), which occurs when complement-mediated pathways are disordered, and secondary HUS resulting from malignancy, infection, and autoimmune dysfunction such as SLE/APS. All complement-mediated TMAs involve abnormal activation of the terminal complement subunit, causing tissue injury8.

Traditionally, autoimmune TMA is treated by treating the underlying condition. Initial treatment may include anticoagulants and/or glucocorticoids. Severe cases may need plasma exchange or IV immunoglobulin (IVIG). TMA can progress quickly despite aggressive measures9.

Conclusion

Patients with organ enlargement, cytopenias, abnormal lab abnormalities (particularly ferritin, triglyceride, and LDH), coagulation problems, liver disorders, and antibiotic-resistant fever should be tested for MAS.

Despite being rare, macrophage activation syndrome and aHUS secondary to SLE cause more ICU admissions and in-hospital death. High-ferritin, elderly, and SLE patients need care. Early MAS workup and care may be needed for complications. Clinicians and hematologists need clearer diagnostic and therapeutic criteria.

Disclosures

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.